Yurts have been a distinctive feature of life in Central Asia for at least three thousand years. The first written description of a yurt used as a dwelling was recorded by Herodotus of Halicarnassus, who lived in Greece between 484 and 424 BC. Herodotus, who is regarded as the father of history, was the first person in the world to record an accurate account of the past. He described yurt-like tents as the dwelling place of the Scythians, a horse riding-nomadic nation who lived in the northern Black Sea and Central Asian region from around 600 BC . Thus, the yurt was described in the first historical document in the world.

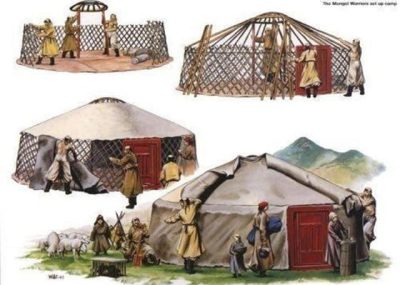

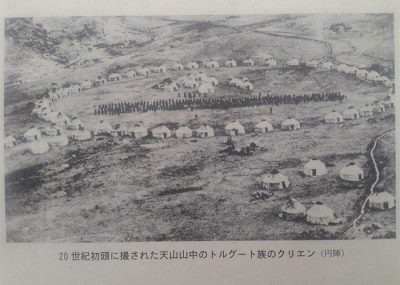

Yurts have been continually in use since this time as a habitation for the Mongolian nomadic peoples of the Central Asian Plateau. Archeological evidence proves that the first empire of steppe warriors in Central Asia, the Huns, who were active from the 4th to the 6th century AD, used yurts as their principal dwellings.

…Great Chinggis (Genghis) Khaan gave the following order:

“…Formerly, I had eighty men to serve as dayguards, Now, by the strength of Eternal Heaven, my power has been increased by Heaven and Earth and I have brought the entire people to allegiance, causing them to come under my sole rule, so now choose men to serve on roster as dayguards from the various thousands and recruit them for me.”

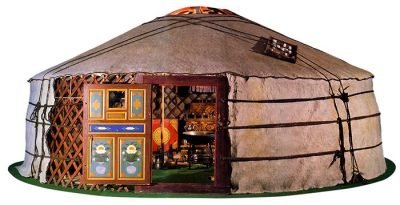

…”The nightguards at night lie down all around the Ger [Yurt] Palace; you, nightguards who stand guarding the door, shall hack any persons entering at night until their heads are split open and their shoulders fall apart, then cast them away. If any persons come at night with an urgent message, they must report to the nightguards and communicate the message to me while standing together with the nightguards at the rear of the Ger[Yurt].”

…”Entering into and going out from the Ger [Yurt] Palace must be regulated by the nightguards. At the door, the doorkeepers from the nightguards shall stand right next to the ger [yurt]. Two from the nightguards shall enter into the ger [yurt] and oversee the large kumis pitchers.”

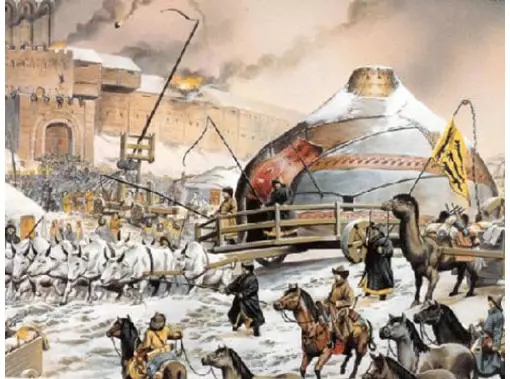

…”The campmasters from the nightguards shall go before Us and set up the Ger [Yurt] Palace. When We go falconing and hunting, the nightguards shall go falconing and hunting with us; but exactly one half of them shall stay at the carts.”

Other accounts related to ger (yurt) include:

Altan Huchar, and Saca Beki, all of them having agreed among themselves, said to Temujin, “We shall make you khan. When you Temjin become khan, we

As vanguard shall speed

After many foes: for you

Fine-looking maidens and ladies of rank,

Palatial gers (yurts), and from foreign people

Ladies and maidens with beautiful cheeks,

And geldings with fine crops

At the trot we shall bring ….”

After they made Temujin Chinggis (Genghis) Khan … Subetei baatar (warrior Subetei) spoke:

…I shall be a felt covering,

And with the others

I shall try to make a cover for you;

I shall be a felt windbreak,

And with the others

I shall try to shelter you

From the wind on your Ger [Yurt].

…Carpenter Gukuchur spoke

“I shall not let the linchpin slip

Off a lock-cart;

I shall not let an axle-cart collapse

On the road

I shall manage the tent-carts”

…Cilaun Qayichi with this two sons Tungge and Qasi also came to pay homage to Chinggis(Genghis) khan and spoke thus

“Let them guard

Your golden threshold”, so saying

I give you these sons of mine;

If they depart from your golden threshold,

Put an end to their lives and

Cast them away

“Let them lift for you

The wide felt door”, so saying,

I give them to you;

If they desert you wide door,

Kick them in the pit of the stomach and

Cast them away”